As the aviation industry charts its course into the mid-21st century, a central question looms: how will commercial air travel, one of the fastestgrowing sources of carbon emissions, reconcile its burgeoning expansion with the global push for net-zero emissions? The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) codified an ambitious target at its 41st Assembly in 2022: to achieve net-zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2050. While this goal signals the sector’s commitment to climate responsibility, new analysis indicates the path to net zero is far from straightforward, and much of the sector’s current trajectory may not be aligned with this vision.

A report by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) offers a sobering look at the carbon footprint of aviation in the coming decades. It models three potential decarbonisation scenarios: business as usual, an optimistic scenario centred on sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), and an even more ambitious approach that combines SAFs with fuel efficiency improvements. The findings suggest that without substantial changes to the way aircraft are produced, fuelled and operated, the aviation sector could rapidly exceed its share of the global carbon budget, leaving airlines, manufacturers and regulators with difficult choices ahead.

The carbon conundrum

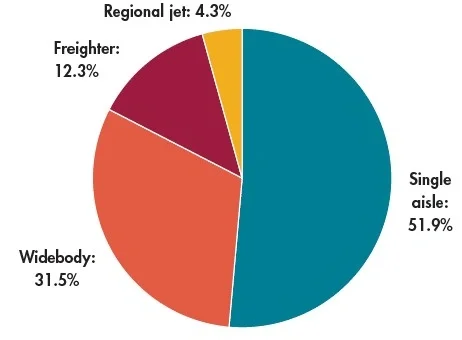

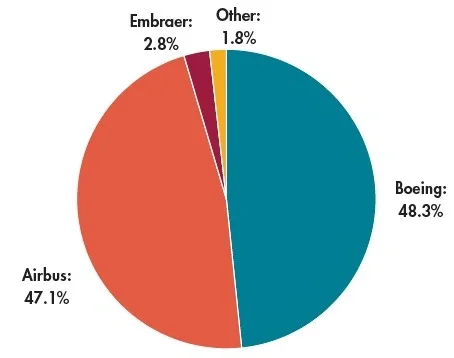

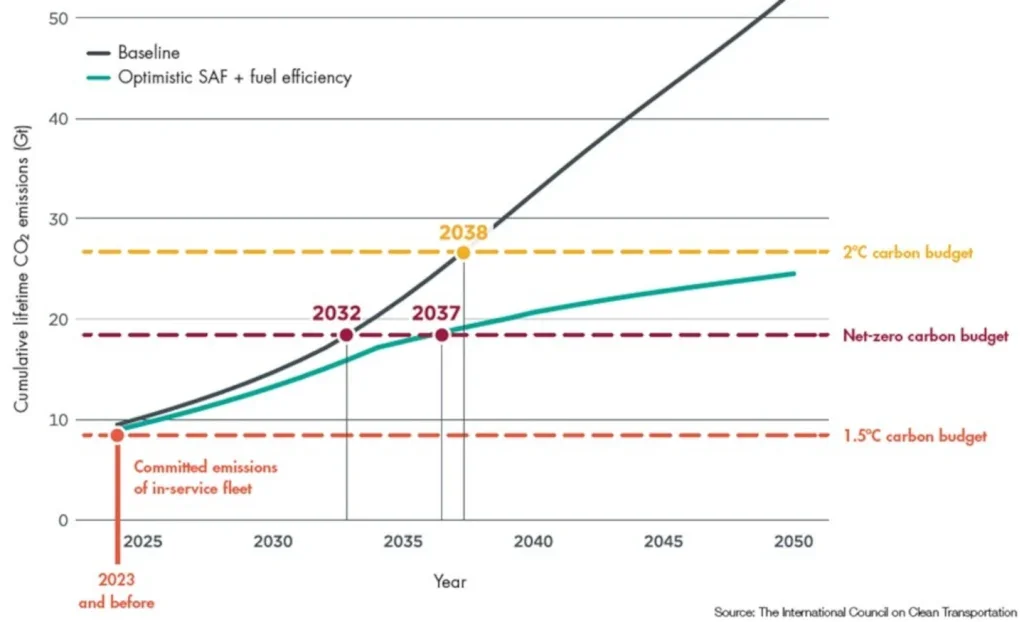

The commercial aviation fleet is set to double in size over the coming decades, driven by increasing passenger demand and economic growth. With this rise in fleet size comes a corresponding increase in carbon emissions. In 2023 alone, the in-service fleet is projected to emit approximately nine billion tonnes of CO2 over its remaining lifetime – nearly half of the entire net-zero carbon budget of 18.4 billion tonnes allocated for the sector. This carbon budget was derived from an average of four industry decarbonisation roadmaps and represents aviation’s contribution to a global warming target of no more than 1.5°C or 2°C above pre-industrial levels. The ICCT report highlights that if current trends continue, the emissions from new aircraft deliveries will likely exhaust the remaining budget between 2032 and 2037, depending on the scenario.

Committed emissions from the 2023 in-service fleet by aircraft class (left) and manufacturer (right), baseline scenario

This suggests that without rapid and aggressive action, the aviation industry’s net-zero target may be unattainable, with all new aircraft delivered after the mid-2030s needing to emit zero CO2 over their entire operational lifetimes to stay within budget.

A central solution?

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) represent the aviation sector’s most promising pathway to reducing emissions. According to the ICCT, SAFs are expected to account for more than half of the CO2 mitigation necessary for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. SAFs are produced from renewable sources, such as biomass or recycled carbon, and can significantly reduce life-cycle CO2 emissions compared with conventional fossil jet fuel. Yet, while SAFs hold great potential, their current use is limited by both technical and economic barriers. Today’s aircraft are certified to use SAF blends of up to 50%, with full SAF compatibility still in the testing phase. Furthermore, the production of SAFs remains relatively small-scale, and costs are significantly higher than conventional jet fuel. Scaling up SAF production to meet future demand will require coordinated efforts across governments, industries and fuel producers.

In an optimistic scenario, where SAFs are aggressively implemented, emissions from new aircraft deliveries could be reduced by 50% compared with a business-as-usual scenario. However, even under this scenario, the aviation sector would still exceed its carbon budget by 2037. This indicates that while SAFs are crucial to reducing emissions, they are not a silver bullet. The aviation industry must look beyond SAFs to additional mitigation strategies, such as improving fuel efficiency and developing zero-emission aircraft (ZEPs).

Aircraft efficiency and zero-emission technologies

Aircraft manufacturers have made notable strides in improving fuel efficiency over the past several decades. Modern aircraft are up to 15% more fuel-efficient than the models they replace. Yet, the sheer growth of the global fleet has outpaced these efficiency gains. Many new aircraft support additional traffic rather than replacing older, less efficient planes, leading to a net increase in emissions.

The ICCT report underscores that new, more efficient aircraft types, coupled with increased use of SAFs, can delay the depletion of the aviation carbon budget. However, this approach still falls short of ensuring that the sector will meet its net-zero goals. By 2034, the report anticipates that emissions from new deliveries will begin to decrease, thanks to more fuel-efficient designs and greater SAF usage. But this timeline leaves little margin for error – any delays in technological advancements or SAF adoption could push the sector over its carbon budget sooner than expected.

Looking to the future, zero-emission planes (ZEPs) powered by hydrogen or electricity offer a potential long-term solution. While these technologies are still in their infancy, they could play a critical role in decarbonising aviation beyond 2040. According to the ICCT, hydrogen-powered aircraft could account for 21% of total aviation energy use by 2050, though they are only projected to contribute about 5% to cumulative CO2 mitigation due to the gradual pace of adoption. For ZEPs to make a meaningful impact, manufacturers must accelerate their development and integration into the global fleet.

Scope 3 emissions and corporate accountability

The aviation industry’s carbon footprint extends far beyond the fuel burned during flights. Scope 3 emissions – the indirect emissions produced throughout a product’s entire life cycle – account for more than 90% of an aircraft’s lifetime emissions. This includes emissions from the manufacturing process, the production of aviation fuel and the maintenance and operation of aircraft over decades of service.

Consumption of aviation carbon budget from cumulative lifetime emissions of projected fleet

In recent years, corporate emissions disclosure has become a focal point for investors, regulators and environmental advocates. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the EU have both introduced regulations requiring large corporations to disclose their Scope 1 and 2 emissions (those from direct operations and purchased energy). However, Scope 3 emissions, which are the most significant in aviation, are not yet mandated for disclosure in all jurisdictions. In 2024, the SEC finalised its ruling on corporate emissions disclosure, which, while comprehensive, stops short of requiring Scope 3 emissions reporting. In contrast, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive mandates that corporations, including aircraft manufacturers, disclose their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. These regulations mark a significant step towards greater transparency and accountability in the aviation industry, enabling investors to better assess the climate risks associated with new aircraft deliveries and fleet operations.

Challenges ahead and the way forward

Aircraft manufacturers face a complex challenge as they seek to balance the need for fleet growth with the imperative to reduce emissions. Over the next two decades, Boeing, Airbus and Embraer are expected to deliver more than 40,000 new aircraft, primarily to support fleet renewal and accommodate rising air traffic. However, under current projections, only about 24,000 of these aircraft can be delivered before the aviation sector exceeds its net-zero carbon budget.

This stark reality places immense pressure on manufacturers to innovate and transition to producing net-zero aircraft. According to the ICCT, at least 10,000 new aircraft delivered by 2042 will need to be powered by hydrogen, electricity or 100% SAF to align with net-zero goals. Beyond that, all new aircraft delivered after 2042 must be net zero to avoid exceeding the carbon budget.

Even with aggressive action on SAFs, fuel efficiency and ZEPs, the aviation industry will likely still produce residual emissions that need to be addressed. Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies, such as direct air capture (DAC), offer one potential solution to offset these emissions. However, the scale of CDR required to neutralise aviation’s emissions is daunting. Under the ICCT’s baseline scenario, approximately 22 billion tonnes of CO2 would need to be captured by DAC to offset emissions from aircraft delivered through 2042 – a volume that is far beyond current or projected global CDR capacity. This underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to decarbonisation. While SAFs and fuel-efficiency improvements can significantly reduce emissions, they must be complemented by broader systemic changes, including investments in CDR, advances in ZEP technology, and stricter regulatory frameworks to ensure that aviation remains within its carbon budget.

The path to net-zero emissions by 2050 is fraught with challenges, and current trajectories suggest that the sector is at risk of exceeding its carbon budget well before mid-century. To meet its climate commitments, the industry must embrace a multipronged strategy that includes aggressive SAF adoption, improved fuel efficiency, the development of zero-emission aircraft and the scaling up of carbon removal technologies. For airlines and manufacturers alike, the next decade will be pivotal. Decisions made now regarding aircraft production, fuel sourcing and technological innovation will determine whether the sector can truly align with global climate goals or whether it will contribute to the planet’s warming trajectory.